The action in this week’s episode kicks off when J.J. reveals to his parents that he has a patron who is helping him purchase art supplies and is providing a space where J.J. can paint. The patron is local businessman and boutique owner Leroy Jackson, who just happens to be a former friend of James’s. Twenty years earlier, before James and Florida got married, James and Jackson had planned to go into business together; James gave Jackson $250, but Jackson gambled and lost the money at the races. When Jackson shows up at the Evans home, James refuses to listen to anything that he has to say and throws him out of the apartment. J.J.’s angry response to his father’s action leads to an argument and J.J. winds up leaving home, moving into the storage room above Jackson’s boutique. James stubbornly maintains his viewpoint, even as Thelma and Michael express how much they miss their brother, and despite Florida’s pleas for J.J. to be allowed to return. After a few days, Florida – under the guise of going to church – secretly goes to visit J.J. While she’s there, James shows up as well, claiming that he’s looking for a missing shirt. While they’re there, Leroy Jackson enters and insists on saying to James what he wanted to tell him 20 years earlier: that he’s sorry. Ultimately, the apology is accepted, Jackson vows to continue helping J.J. with his painting endeavors, and James tells J.J. he can come back home.

I’m beginning to see a pattern that, as much as I’ve watched this show over the decades, I never really noticed until I started analyzing each episode for this blog. James is consistently depicted as obstinate, illogical, quick-tempered, and unreasonable, while Florida is even-tempered, rational, patient, and sensible. This episode is no different. Don’t get me wrong – James’s stubbornness has always been an unmistakable character trait; I suppose I just didn’t realize how frequently it played into the plots of the various episodes.

Here, James places a 20-year-old feud above the well-being and potential success of his oldest son (not to mention the child who is most in need of a leg up), while not only Florida but both of the younger children try in vain to point out the error of his ways. Florida, in fact, literally tells her husband, “You did the wrong thing.” The episode even features a scene with James interacting with God – and coming out with egg on his face. After Florida insists that the Lord will punish him for his disrespect, James gives God 10 seconds to show him a sign. Before the time is up, James’s watch stops working!

Although James continues to maintain his stance against J.J. returning home, the admonitions of his family obviously get through to him, as evidenced by his showing up at J.J.’s temporary home with a flimsy excuse. It’s clear that James is concerned about his son and wants him back, but it’s not until after Jackson apologizes and shakes James’s hand that he pushes his pride aside and relents.

Pop Culture References:

Miss Black America and Moms Mabley

The episode opens with J.J. sleeping on the couch. His face first indicates that he’s enjoying his dream, but his expression then changes to one of distaste. When he awakens, he explains to Florida that he was dreaming that he’d been commissioned to paint the winner of “Miss Black America” in the nude – but the winner was Moms Mabley!

Miss Black America was a beauty pageant created in 1968 as the answer to the Miss America pageant; at that time, there had never been a black Miss America contestant. In the early years of the Miss America pageant, one of the rules stated that contestants “must be of good health and of the white race.” Even though this rule was abandoned in the 1940s, there wouldn’t be a black contestant until 1971, when Cheryl Browne Hollingsworth represented the state of Iowa in the pageant. The Miss Black America pageant was produced by Philadelphia businessman J. Morris Anderson; the first pageant was held in Atlantic City on the same day as the Miss America event. The Miss Black America pageant was held every year until 1996. It started again in 2010, and was held sporadically in the years since, with the last pageant, as of this writing, taking place in 2018.

Moms Mabley in the nude.

Moms Mabley was a popular black comedian born Loretta Mary Aiken in 1894. She began her career in vaudeville, gaining popularity as “Jackie Mabley” on the Chitlin’ Circuit, a collection of venues that catered to black performers and audiences. She adopted the name “Moms” in the 1950s and took on the persona of a toothless older woman, performing in a bucket hat, housecoat, and colorful knee socks. She went on to play such venues as Carnegie Hall and on television shows like The Smothers Brothers, The Ed Sullivan Show, and The Pearl Bailey Show. She died of heart failure in 1975.

The “Ugly” Green Giant

When Thelma almost uses a tube of J.J.’s green paint as her shampoo, he jokes that if she were shorter, she would have been the first black leprechaun. Thelma counters by telling J.J. that if she spilled some paint on him, he would be known as the “ugly Green Giant,” and adds, “Ho, ho, ho.” This is a reference to the Green Giant frozen vegetable products, which had a series of popular commercials featuring the company’s brand mascot, the Jolly Green Giant. The giant never spoke, except to say, “Ho, ho, ho.”

Guest Stars

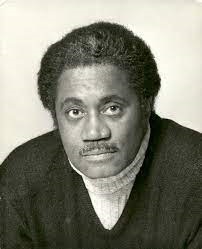

Edmund Cambridge (Leroy Jackson)

A native of Harlem, New York, Edmund James Cambridge, Jr., was born on September 18, 1920, and, according to legend, got his first taste of show business by sneaking out of his house at the age of 15 to perform at Smalls Paradise nightclub. In Los Angeles during the early 1960s, Cambridge founded the Cambridge Players, a performing troupe whose membership included Juanita Moore, Helen Martin, Esther Rolle, Isabel Sanford, and Beah Richards. The troupe produced the James Baldwin play The Amen Corner, which premiered on Broadway in 1965.

A few years later, Cambridge became a founding member of the Negro Ensemble Company; one of the group’s first plays, Ceremonies in Dark Old Men, was directed by Cambridge and landed him a Drama Desk Award. He also co-founded the Kilpatrick-Cambridge Theater Arts School in Los Angeles in 1971. Around this time, he made his television debut on the short-lived drama series Bracken’s World, and during the next few decades, he would go on to appear on such television series as Kojak, Adam-12, Family Matters, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, and The Bernie Mac Show. He was also seen in big screen features like Friday Foster (1971) and Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey (1991). Between appearances in front of the camera, Cambridge (who was a cousin of stand-up comedian and actor Godfrey Cambridge) continued his stage work; in 1984, he directed the original production of 227, a play by Christine Houston that later became the popular NBC television show of the same name starring Marla Gibbs.

A longtime resident of Los Angeles, Cambridge died in 2001 of complications from a fall he suffered while visiting relatives in Harlem. He was 80 years old. The eulogy for his funeral service was conducted by actress Della Reese; Cambridge had been a member of Della Reese’s church, Understanding Principles for Better Living.

Other stuff:

In this episode, we see the brief revival of the show’s early depiction of J.J. as a thief. It comes up when Florida shares with James her concern about how J.J. has been getting new art supplies. (“I hope he hasn’t been finding things again,” she says.)

I’ve been wondering . . . did James ever get his money back from Leroy Jackson? He certainly should have received more than Jackson’s heartfelt apology. Given Jackson’s suit and coat, his sharp shoes, and that rock on his finger, he’s obviously not hurting for money. While he was handing out “I’m sorrys,” maybe he should have also been passing out some Benjamins.

I always found it funny that James merely had to hear that the last name of J.J.’s patron was Jackson, and he immediately jumped to the (correct) conclusion that it was Leroy Jackson, his ex-pal. I could understand his suspicions being aroused if the man’s last name were, say, Boykin or McCullough or Underwood. But Jackson? That was quite a leap.

This episode contains the first time that we see some real sibling support between J.J. and Thelma – the two are usually at each other’s throats, trading insults like they were baseball cards. When James tells Leroy Jackson to leave, Thelma implores, “Daddy, don’t throw him out – he wants to help J.J.’s career!” And later, after Jackson departs, Thelma chastises her father, telling him that this was a big chance for J.J.: “The people could have discovered his talent! (Even J.J. is shocked, asking, “Do my ears deceive my face?”)

Incidentally, the business that James and Leroy Jackson planned to go into is never named.

~ ~ ~

The next episode: Junior the Senior . . .