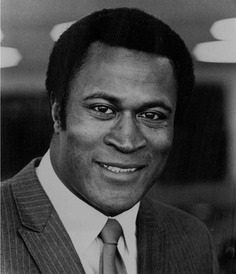

Fifty years ago today, on February 8, 1974, Florida and James Evans, their children J.J., Thelma, and Michael, and neighbor and friend Willona Woods, made their debut on American television on Good Times. The series was only on for five seasons, but it continues to entertain fans with its insightful writing and first-rate performances from the cast and guest stars.

To celebrate this momentous 50-year milestone, I am offering 50 things I love about Good Times, including memorable quotes, favorite episodes, and much more. I hope you’ll let me know in the comments what you love about this groundbreaking show!

- “Well, it’s comforting to know there’s still some respect for Black Power around here.” – Florida’s first line in the show’s pilot episode.

- “Boy is a white racist word.” We heard this declaration from Michael in several of the early episodes.

- Florida, Thelma and Willona’s performance of “Stop, in the Name of the Love” in “The Rent Party” (Season Three). It’s a delight.

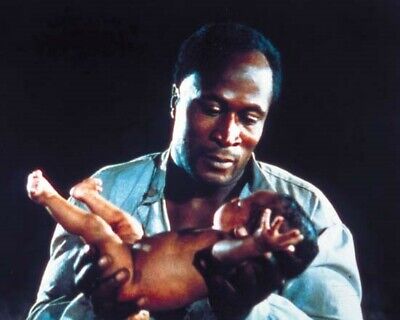

- Janet Jackson’s four-episode introduction to the series as Penny at the start of Season Five. I’ll never forget when it first aired – everyone I knew was watching and talking about it.

- Seeing guest appearances from performers who went on to be stars, like Roscoe Lee Browne, Judy Pace, Brenda Sykes, Jay Leno, Alice Ghostley, Ron Glass, Charlotte Rae, and Debbie Allen.

- The way the show addressed real-life issues like teen drinking, gang violence, teen pregnancy, hypertension, and venereal disease.

- The live studio audience – their responses were part of what made the show so memorable – not just the laughing and clapping, but other reactions like shocked gasps and audience members calling out, “Right on!”

- Ralph Carter having the opportunity to display his singing talent in several episodes, including “The Rent Party” and at Thelma’s wedding.

- The theme song. I’ve heard it countless times and still can’t help singing along.

- Willona’s collection of wigs. She had a different look in practically every episode! (One of my favorites was her afro in “Sex and Evans Family.”)

- Ernie Barnes’s paintings. This talented artist was behind most of the artwork on the show that was presented as J.J.’s.

- James’s patented responses in place of the word “yes,” like, “Is fat meat greasy?” and “Is an elephant heavy?”

- James’s brown corduroy pants. (What can I say?)

- The first three seasons. There’s no denying that the series was never the same after John Amos left, but the three seasons that he was on the show were absolute gold.

- “Where There Smoke” from Season Five, a Rashomon-type episode where J.J., Thelma, Michael, and Penny each give their own accounts of how the family sofa caught on fire. It’s hilarious (and the only episode after Season Three that I’ve seen multiple times).

- “The Dinner Party,” from Season Two, where a senior citizen friend of the Evans’s has fallen on hard times, and the family believes that she has brought a meat loaf made of dog food to serve at dinner. This is one of the many episodes that expertly walks a fine line between presenting a serious issue and being incredibly funny.

- “Bon appetit, y’all!” Willona in “The Dinner Party” (Season Two)

- The ideal role model provided by Thelma. She wasn’t just pretty, but she was also smart, talented, ambitious, fearless (I loved the way she stood up to Mad Dog in the “The Gang” episode), and she could put J.J. in his place every time.

- Having two former members of the 1930s Little Rascals on the show: Stymie Beard and Ernest “Sunshine Sammy” Morrison.

- “Sir? Can I ask you just one question? Who IS looking for the guy who shot Medgar Evers?” – Michael, talking to the FBI agents looking for Florida’s nephew in “Cousin Cleatus” (Season Three)

- “The Debutante Ball” episode, which included an interesting depiction of a couple who’d made it out of the ghetto, but forgotten from whence they came.

- The many Chicago references, like Mayor Richard J. Daley, Marshall Field’s department store, and the Chicago Defender newspaper.

- The loving relationship between James and Florida. There was a reason why Willona called them the “Liz and Dick of the Ghetto” – these characters were clearly still in love, and showed it often through their affection for each other. It was beautiful to see.

- The way James called Florida “baby.”

- “The kitchen and the bedroom, Florida, the kitchen and the bedroom!” – James in “Florida Flips” (Season Two)

- “You know what I’m gonna leave the world when I go, Florida? A tombstone that reads “Here lies James Evans. Back in the hole again.” – James in “Florida’s Rich Cousin” (Season Three)

- “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways. I love you for your skin’s pure sheen, for your two sweet lips, with teeth in between.” – J.J. to Marcy Jones in “My Son, the Lover” (Season One)

- “Those coulda been Sweet Daddy’s drawers!” – James in “Sweet Daddy Williams” (Season Three), where the flamboyant numbers runner hires J.J. to paint his girlfriend, Savannah Jones.

- “The elevator ain’t workin’” in “The Visitor” (Season One). This line was said by nearly every character in the episode and whenever I see it, I say it right along with them!

- “Now that’s the kind of religion I can get into. The good word rolls out and the long green rolls in!” – J.J. in “God’s Business is Good Business” (Season One)

- “Florida the Woman” episode, where Florida’s boss Oscar Harris (Thalmsus Rasulala) brightens Florida’s day after an especially frustrating morning with James and the children. One of my favorite scenes is when Oscar and James come face to face and James can’t suppress his jealousy.

- “The TV Commercial” episode, featuring a particularly funny bit with J.J. and James, where they present a faux commercial of their own.

- Willona’s wardrobe. Some of her outfits were so sharp, they could be worn today!

- The fact that Willona was content being single. It was so refreshing when, during a conversation with Florida, she declared that there was “a big difference between being alone and being lonely. And the one thing I ain’t is lonely.”

- Mention of popular Black performers like Diana Ross, Redd Foxx, The Isley Brothers, The Jackson Five, Harry Belafonte, Isaac Hayes, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield, and Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes.

- J.J.’s love for Thelma, despite their constant arguing. This was demonstrated in numerous episodes, including his defense of her engagement to Larry (Carl Franklin), and his protective reaction after she was attacked in the “Family Gun” episode.

- Florida’s constant support of James – like in “Too Old Blues” when James missed out on a job opportunity because of his age, or “The Mural,” where the family learns that James had spent Thelma’s college fund.

- “If she gets any happier, she’s gonna break every dish in the house.” – J.J. in “Florida Flips” (Season One)

- “The Family Gun” episode, which had an especially chilling ending, when Michael shoots his father’s gun into the air after mistakenly thinking that he’d removed the bullets.

- “She hit her husband? Free at last, free at last! You’re halfway there, sister.” – Wanda (Helen Martin in “Florida Flips” (Season One)

- “Thelma’s Young Man,” where Lou Gossett guested as the balding, 40-something boyfriend of 17-year-old Thelma.

- “The Lord is my German Shepherd.” – J.J. in “The Dinner Party” (Season Two)

- “If you want that button sewed, you sew it yourself. And if you want breakfast, make it yourself. Then make the lunch for the children. Wash the dishes, do the laundry, make the beds and sweep the floor. And see how you’d like being mother, housewife, diplomat, referee, counselor, cook, seamstress, and sparring partner, with no pay and no fringe benefits!” – Florida in “Florida the Woman.”

- “Damn, damn, damn!” Florida’s unforgettable reaction in “The Big Move, Pt. 2,” when she finally allows herself to feel the pain of James’s untimely and unexpected death. (Season Four)

- The “Thelma’s Scholarship,” episode, where Thelma is sought as the “token” in an all-white sorority at a Michigan boarding school.

- The lines said and situations depicted on the show that simply could not be aired today, like James using the “N” word or delivering a whooping to Michael’s classmate.

- The way James bravely, and with no hesitation, protected his family. One instance that comes immediately to mind is his confrontation in “Cousin Cleatus” with Florida’s nephew, who planned to use Michael as a hostage (or worse yet, a shield).

- Scenes that make me laugh every single time, no matter how often I’ve seen them – like when James cracks up in “My Son, the Lover” after hearing J.J. reading his poem to Marcy Jones, or in “Sex and the Evans Family” when Michael asks if the item Florida’s hiding has anything to do with Black unity and Willona responds, “In a way.” Florida’s silent slow burn is a masterpiece!

- The show’s use of terms I remember from my childhood, like “blister your behind.”

- “Have mercy!”