In this episode, James has just received word that he has passed the written aptitude test for a union apprentice training program and is scheduled for an interview. If he’s accepted, he’ll earn $2.50 an hour as an apprentice, and upon completion of the program, he’ll receive $4.25 an hour. Before leaving for his interview, James tells Florida to use their rent money for a party to celebrate his new job. During the interview, while going over James’s application, the interviewer discovers a computer error; the application states that James is 31 years old, but he’s actually 41. Because the government-funded apprentice program is for men ages 18 to 35, James is too old to be accepted. When James arrives home, the party he requested is in full swing, complete with guests. He looks sheepish as he’s serenaded by the group’s rendition of “He’s a Jolly Good Dude,” and his discomfort grows as Thelma and J.J. talk about all the things they’d like to buy with James’s new salary. He finally shares that he didn’t get the job, but Florida offers words of support and encouragement, leading James to philosophically conclude: “So I missed out. What’s the big deal? What would it have meant anyhow? Some more spending money, fancy clothes, nicer place to live? What do I need with a union job for when I have you and these kids?” He and Florida embrace, but James rather plaintively adds, “But it sure would’ve been nice.”

Between the laughs, and the surfeit of pop culture references (see below), this episode serves to underscore the close-knit, caring nature of the Evans family. There’s the excitement and pride over James’s new employment prospects but, more importantly, it’s the family’s reaction when they learn that he didn’t get the job. After James shares his disappointing news with the partygoers, he leaves the room with Florida, and the three children commiserate in their own little group. “Whoever said he was too old don’t know Daddy,” J.J. offers, and Michael adds, “I’d like to see the dude who called him too old. I’d tell him about some of those not-too-old whippings he’s laid on me.” Thelma has the last word: “Daddy ain’t too old. He could do that job at the union. He could do anything anybody gave him a chance to.” And even though James expresses concern that he has disappointed Florida, she bolsters his spirits with her uplifting response: “James, you always see this family through,” she tells him. “You can do it.” The episode sees the family experience a hopeful start only to plummet back to earth in worse shape than they’d been before, but the message is that together, they will always find a way.

Pop Culture Connections

Energy Crisis

While hugging Florida (more on this below under “Other Stuff”), James states that he doesn’t have to worry about “that energy crisis” because he has his “own personal heating system” (meaning Florida.) The energy crisis James is referring to was caused by the action taken by the Arab members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, who imposed an embargo against the United States. This was in retaliation for the U.S. decision to re-supply the Israeli military and to gain leverage in the post-war peace negotiations. Embargoes were also enacted against other countries who supported the Israelis, including the Netherlands and South Africa. As a result of the embargo, the U.S. saw skyrocketing prices for gasoline and fuel oil. The embargo, which started in October 1973, ended in March 1974, about a month after the episode aired.

Wilt Chamberlain

After the “personal heating system” comment, Florida observes that a good looking man like James could have married any woman in Chicago, and he responds, “True. But I married you.” Florida rejoins, “If that’s a compliment, I’m Wilt Chamberlain.” Chamberlain was a seven-foot, one-inch basketball star who joined the National Basketball Association (NBA) in 1959, when he signed on with the Philadelphia Warriors (which later relocated to California to become the San Francisco Warriors). During his career, he would also play for the Philadelphia 76ers and the Los Angeles Lakers and would play on two NBA championship teams. Chamberlain retired from basketball in 1973.

Meat Shortage

At breakfast, Thelma complains about the family eating oatmeal again, and Florida tells her that she should be grateful for the oatmeal or any other food on the table. “Remember,” she adds, “this family got through the meat shortage without even knowing there was one.” The term “meat shortage,” while commonly used at the time, is a misnomer. In the early 1970s, there was a blight in corn crops that started in Florida and spread north and west, resulting in an increase in corn prices. Concomitantly, livestock producers began to cut back on their herds, leading to a reduction in beef production and a spike in beef prices. This led to price gouging and even a meat boycott; there was no shortage, per se, but meat was inordinately expensive. After a few years, the blight faded, corn prices fell, livestock was rebuilt, and prices returned to normal.

Ozzie and Harriet

When Thelma and J.J. argue about the amount of time she spends in the bathroom, James complains about the frequency of the arguments between the siblings and Florida remarks, “Let’s face it, James – this family ain’t Ozzie and Harriet.” The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet was an ABC-TV sitcom that aired from 1952 to 1966 and starred the real-life family of actor/bandleader Ozzie Nelson, his wife, singer Harriet Nelson, and their sons, David and Ricky. The series was typified by the family’s wholesome relationship and homespun lifestyle.

Aristotle Onassis

For his celebration party, James tell Florida that he wants barbecued chicken and ribs, champagne, and music, and jokes that she can hire The Temptations. “Hold on there, Onassis,” Florida says. “What do I use for money for this orgy?” Florida was referring to Aristotle Socrates Onassis, the Greek shipping magnate who was, at that time, one of the wealthiest men in the world. In 1968, he married Jacqueline Kennedy, the widow of President John F. Kennedy. Onassis died in 1975 at the age of 69.

Rodney Allen Rippy

In an allusion to J.J.’s penchant for thievery, Willona refers to him as “Rodney Allen Ripoff.” This is a takeoff of the name of a child actor who became popular in the 1970s for his appearances in commercials for fast-food chain Jack-in-the-Box. (Jack-in-the-Box was the first fast-food restaurant to popularize drive-thru ordering via a two-way intercom system. These restaurants featured a clown head on top of an intercom, with a sign that read, “Pull forward. Jack will speak to you.”) Rippy would later guest on numerous television shows, present with Michael Jackson and Donny Osmond at the American Music Awards, and sing “Take Life a Little Easier,” a record released by Bell Records in 1973 based on one of Rippy’s Jack-in-the-Box commercials.

Diana Ross

While joking about the type of party he wants for his celebration, James tells Florida not to book The Temptations but, instead to hire “The Supremes – and WITH Diana Ross!” The Supremes was an all-girl musical group that was popular during the 1960s, comprised originally of Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, and Florence Ballard. (Ballard was fired from the group in 1967 and replaced by Cyndy Birdsong.) Almost from the beginning, Ross emerged as the main singer, and in 1970, she left the group to pursue a solo – and wildly successful – career.

Soul Train

Thelma is responsible for providing the music for the party that her father requested – she explains to Florida that she;s gotten albums by Isaac Hayes, The Jackson Five, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield, and Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes. Florida quips, “When he said ‘music,’ he didn’t expect you to hijack Soul Train.” Soul Train was a popular musical variety show that premiered on WCIU-TV in Chicago in 1970, created by Don Cornelius, who was also the show’s executive producer and host. Airing live on weekday afternoons and sponsored by local Chicago-based retailer Sears, Roebuck and Company, the show featured acts by popular R&B and soul acts, and local teens and young adults were shown dancing to the music – the first episode on August 17, 1970, featured Jerry Butler, The Chi-Lites and The Emotions as guests. The program was an immediate hit, attracting the notice of another Chicago company, the Johnson Products Company, which co-sponsored the show’s expansion into syndication. Seven other cities purchased the program: Atlanta, Birmingham, Cleveland, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia, and by the end of its first season, the show was airing in 18 additional markets. In October 1971, when the program moved into syndication, it began airing weekly and its home base moved to Los Angeles. Cornelius moved west as well, but for a while, a local version of Soul Train continued to air in Chicago, with Cornelius briefly hosting both programs before focusing solely on the Los Angeles show. The show’s Chicago version continued to air every weekday afternoon until June 1976, hosted by dancer Clinton Ghent, who’d been a part of the show since its inception, and reruns were shown every Friday until 1979. The show was known for two long-running elements: the Soul Train scramble board, where two contestants would unscramble letters to spell out a famous group or singer, and the Soul Train line, a take-off of the 1950s dance, The Stroll. Here, dancers would line up in two lines opposite each other, and dance two at a time down the center of the makeshift aisle. Don Cornelius stopped hosting the syndicated version in 1993, and the show was cancelled after the 2005-2006 season.

Ambassador East

Willona commends Florida on the decorations for the party, telling her that it looks like the Grand Ballroom at the Ambassador East. This was a popular hotel in Chicago that opened in 1926 in the Gold Coast area, near the city’s Magnificent Mile district. It was featured in the 1959 Alfred Hitchcock film North by Northwest, starring Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint, and the hotel’s Pump Room was a magnet for stars including Frank Sinatral, Elizabeth Taylor, and Natalie Wood. It was purchased in 2010 by Ian Schrager, an entrepreneur best-known for being co-founder and co-owner of New York’s Studio 54 nightclub. Schrager renamed the hotel the Public Chicago. The hotel changed hands a few more times and is now known as the Ambassador Chicago, under the Hyatt brand.

What You See is What You Get

Willona also has complimentary words for Michael’s outfit for the party, and jokes that he’ll have to fight off the girls. Michael rejoins, “Well, what they see is what they gonna get,” accompanied by a little swaying type of dance movement and a snap of his fingers. This is reminiscent of a catchphrase and movement used by comedian Flip Wilson in drag as “Geraldine Jones,” a sassy, independent, sexy, and feisty female character that he popularized on his NBC television show in the early 1970s. Also, in 1971, the R&B group The Dramatics released a hit song, “Whatcha See is Whatcha Get.”

Guest Stars

Interviewer: Woodrow Parfrey

Parfrey played the man who interviewed James for the apprentice program. Born Sydney Woodrow Parfrey on October 5, 1922, this prolific actor of stage, screen, and TV was orphaned in his teenage years and worked as a car mechanic before entering the military. He was captured by the Germans in World War II, and upon his release from the Army following the war, he took an aptitude test which indicated that he would be proficient in the acting field. He performed in a variety of stage productions during the 1940s and 1950s, including the Broadway production of Room Service, which closed after only 16 performances despite a cast that included Jack Lemmon and Everett Sloane.

He focused primarily on TV and film beginning in the 1960s; his television credits included appearances on a wide variety of popular shows including Gunsmoke, Perry Mason, Hazel, Quincy, and the pilot for The Waltons, titled The Homecoming: A Christmas Story. On the big screen, he was in such hits as Planet of the Apes (1968), Dirty Harry (1971), Papillion (1973), and The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976). Sadly, Parfrey suffered a fatal heart attack at the age of 61 – the same age his father was when he died.

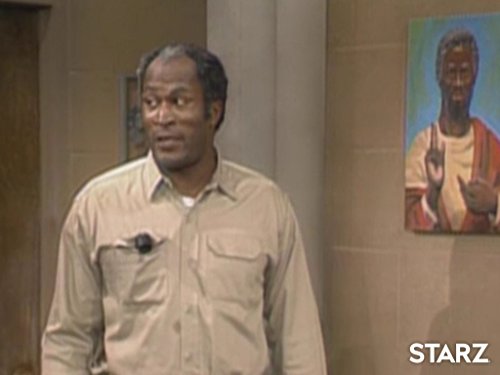

Monty: Stymie Beard

Beard played one of the guests at James’s “celebration” party; he had one line: “Florida, I couldn’t be happier if it was MY wife who got a job!” You can read more about Beard in the post on the first episode of the series.

Other stuff:

Although this was the third episode filmed, it was actually the first one to air.

This is the first episode that makes a reference to Florida’s weight (a running gag that lasted for too long, in my opinion). James gives Florida a hug from behind and remarks, “Gorgeous hunk o’ woman here.” Florida laughingly replies, “I don’t know about the gorgeous, but I’m sure a lot o’ hunk.”

There isn’t an overabundance of lines or situations in Good Times that are cringe-worthy to me, but they do exist and this episode contains the first. James says that he married Florida because she was pregnant but adds that he’s only joking. Michael and J.J. are seated at the dining table nearby and J.J. says, “You mean y’all waited for the preacher to say the word before y’all had me? Don’t spread it around – my friends will never stop jiving me!” So, in other words, most of the families in the community are single-parent households, with an absentee father and children born, as they say, out of wedlock – and this is so much the norm that J.J.’s friends would make fun of him if they knew that his parents were married before he was born. This is patently insulting – and not the last time this type of characterization will come up in the series.

This episode contains numerous references to J.J. being a thief, which was first mentioned in the pilot. J.J. is heading downstairs to get the family’s mail, and Florida warns him not to take any mail that doesn’t belong to them. “I don’t take things, Mama,” J.J. says, “I find them.” Florida admonishes him, saying that God didn’t intend for man to steal, and J.J. asks, “Then how come he gave us more pockets than hands?” Later, when James learns how much he’ll make if he’s accepted into the apprentice program, J.J. remarks, “We gonna be so rich and have so much money, I won’t have to find my art supplies no more!” Before the party begins, Florida sends .J.J. and Thelma to buy potato chips from the local store, and when Thelma asks why she has to go along, Florida explains: “I want the potato chips bought, not found.” And upon his return with the chips, J.J. remarks that he’d been in the store numerous times, but “that’s the first time I’ve ever been involved with a cash transaction.” (Ugh. Talk about overkill!)

We learn in this episode that James dropped out of school after the sixth grade, and that he served in the Korean War. We also learn the name of Willona’s ex-husband: Alvin. That name would change later in the series, though.

Florida is back to conversing with God in this episode – after James leaves for his interview, she looks heavenward and expresses her thanks to the Lord, adding, “In my heart I always knew you was the biggest equal opportunity employer of them all!”

The next episode: God’s Business is Good Business . . .